In 2016, Faruq Bey moved into a one-bedroom apartment in a red brick rowhouse in Washington, D.C. A Cleveland native, Mr. Bey first came to the city to study theater at Howard University. He left after college and bounced around, but he missed the city. When a job running a black box theater at the Anacostia Arts Center came his way, he jumped at it. The nonprofit that ran the arts center rented out several affordable apartments in the neighborhood in southeast Washington, and Mr. Bey settled into one. He painted accent walls — sky blue in the living room, periwinkle in the kitchen. He could imagine staying a while.

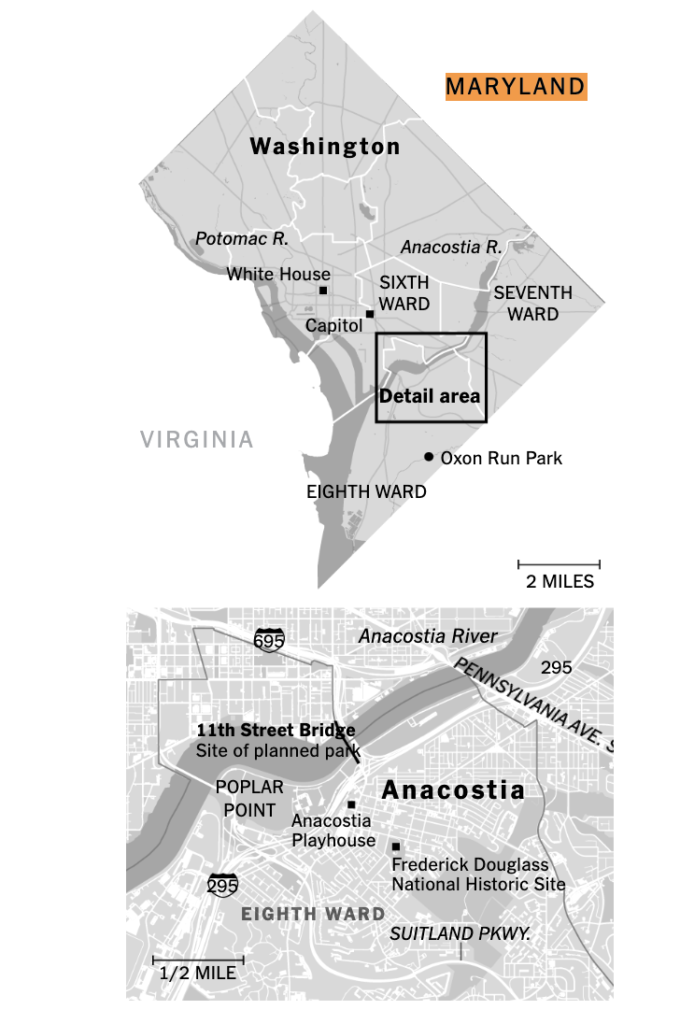

Mr. Bey loved Anacostia. It felt like a small town nestled in a big city. Like Mr. Bey, most of the people who lived there were Black, and he relished the feeling of walking out the door and into a Black community. He took his dog on long walks in the park that ran in a narrow ribbon along the Anacostia River. He’d walk down the waterfront trail and across a new four-lane bridge at 11th Street, lingering to enjoy the breeze and the view from the wide pedestrian walkway or the overlooks built on the piers of an old highway that had once spanned the river.

For Faruq Bey, Anacostia feels like a small town in a big city.

A year or so ago, Mr. Bey read an article about a plan to build an elevated park on those salvaged piers. The 11th Street Bridge Park would repurpose the old infrastructure to create a new civic space, a park and cultural hub, connecting the wealthy, predominantly white neighborhoods of Navy Yard and Capitol Hill with historic Anacostia and Fairlawn, both of which are majority Black and low-income. The idea stirred up conflicting feelings in Mr. Bey. The project would open the riverfront for swimming and kayaking and give people from the neighborhoods a place to meet and hang out. “I was like, OK, this is such an amazing project, right? It’s so dope,” he said. But what made the park so amazing also made it an engine for gentrification.

In the early 2000s, young, mostly white professionals poured into Washington, reversing five decades of population decline. Gentrification swept across the city, transforming neighborhoods like Shaw, the thriving Black community that surrounded Howard University. The wealth gap between white and Black families in Washington was among the most pronounced in the nation, so most of the people getting displaced were Black. Many people headed east to Anacostia and throughout Wards 7 and 8, where housing was more affordable. By 2015, half of Washington’s Black population lived east of the river, where decades of disinvestment and racially restrictive redlining had depressed property values, concentrated poverty and left residents struggling to access basic services.

When Mr. Bey first moved to Ward 8 in 2016, many restaurants in Navy Yard, less than a mile away, wouldn’t deliver to his apartment. One in three families lived below the poverty line. A single grocery store served more than 70,000 residents. The median home value in Anacostia was $256,000, less than half the median across the river in Capitol Hill. Three of every four Anacostia residents were renters. You could almost see the capital flowing east across the bridge park, flooding out people who didn’t own their homes or couldn’t afford an increase in property taxes. Mr. Bey felt protective of his neighbors, worried that people who had lived in the area for decades would be priced out just as the neighborhood was beginning to flourish. “That seems like a system error,” Mr. Bey told me. “Why do we have to move out for everything to succeed and be beautiful?”

LIVE EVENT

How will Anacostia change after 2025?

The New York Times’s Headway team is exploring change and development in Anacostia. The project kicks off in October. If you’d like to join us and share your thoughts, sign up here and we’ll send you details.

The same question occupied Scott Kratz, the director of the 11th Street Bridge Park, for the better part of a decade. Mr. Kratz moved to Washington in 2006 with his wife and bought a house in Capitol Hill, four blocks from the Anacostia River. In his former job as the vice president for education at the National Building Museum, Mr. Kratz had followed the development of the High Line, a 1.45-mile linear park built on an abandoned rail line that ran over the former meatpacking district in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood.

“It’s inevitable that if you’re going to create quality open space, which every community deserves, you may be driving real estate value up in that community,” said Asima Jansveld, the managing director of the High Line Network, which was founded to help other cities learn from the High Line and now includes 38 infrastructure reuse projects across the country. “So the biggest lesson we talk about with new projects is to think really carefully about who’s benefiting from that value.”

When Mr. Kratz set about building a bridge park, he was captivated by the idea of restitching Washington across the river that had long been an economic and racial divide. But he was from elsewhere, part of the wave of newcomers that had reshaped the city. Longtime residents and Ward 8 leaders pressed him to think bigger, beyond the footprint of the bridge itself.

Scott Kratz has been working for a decade to build a park over this section of the Anacostia River.

Public investments in infrastructure have long benefited white communities at the expense of Black ones in particular. Railroads bisected communities, creating some of the first barriers that planners would use to segregate neighborhoods by race. Those segregated neighborhoods, denied access to credit and financing by the federal government in the 1930s, would be targeted for highway construction in the 1960s, displacing hundreds of thousands of Black and Hispanic families.

People in Ward 8 wanted this project, as small as it was, to be different. They wanted it to enrich the Black community that was already there, not accelerate an influx of white people. They wanted the value created by the bridge park to be invested in their neighborhoods. They wanted to own their own homes. They wanted well-paid jobs. They wanted art and music — and artists and musicians as neighbors. They wanted fresh food and safe streets.

It was a lot to ask of a bridge. But Mr. Kratz quickly learned that he couldn’t just build a bridge and ignore the needs of the community that contained it.

The bridge park has yet to be built. Walk down to the waterfront and all you see are those three old piers jutting out of the Anacostia River. But, in another sense, it does exist. A physical landscape — homes, gardens, classrooms — has arisen out of the promise of a park. Over the past decade, Mr. Kratz and many others have tried to build this park differently, grappling at every step with the question that had so troubled Mr. Bey: Whom would it be for?

A mural at the corner of 16th and W Streets in Anacostia painted by Aniekan Udiofia honors Frederick Douglass, who lived in Anacostia when he was U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia.

The Big Chair, built by a local furniture company in the 1950s, has become an Anacostia landmark.

II.

In 1877, when Frederick Douglass bought a house on a hilltop in Anacostia, he was one of the first Black people to own a home in the all-white suburb, mostly occupied by the families of workers employed at the Navy Yard. As U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia, Douglass would walk to work across the Navy Yard Bridge, which spanned the river at 11th Street SE. That bridge was eventually replaced with a crossing that could accommodate streetcars, and then again, in the 1960s, with two four-lane highway bridges connecting the heart of the city to the Maryland suburbs. By then, the formerly white area had become almost entirely Black, as residents displaced by urban renewal projects elsewhere in the city began to move into public housing projects and apartment complexes that public officials had concentrated east of the river.

By the mid-2000s, the District Department of Transportation decided to replace the aging highway bridges. Harriet Tregoning, then Washington’s director of planning, had watched the city become an increasingly fractured place, where neighbors rarely spoke to each other. Nowhere was that divide more apparent than across the river between Wards 6 and 8. She convinced the transportation agency to save one of the bridge’s piers and piles, the supports that extended deep into the riverbed, and started asking anyone who would listen: What about building a park on those piers, a public space suspended over the river to connect the long-divided neighborhoods?

One morning in the spring of 2011, she had breakfast with Mr. Kratz, who wondered, idly, what was happening with the old bridge supports. Ms. Tregoning told him her ambition. Mr. Kratz was a museum educator, not an architect or an urban planner, but the idea struck a chord.

The house Frederick Douglass bought in Anacostia in 1877 is now a national historic site.

Gordon Parks, the legendary photographer, got one of his first assignments, in 1942, documenting life in the Frederick Douglass houses in Anacostia. (Gordon Parks, Farm Security Administration, via Library of Congress)

A few months later, Ms. Tregoning and Mr. Kratz set up a public meeting with Marion Barry, the four-time mayor who was then representing Ward 8 on the D.C. Council, to present their idea. Brenda Richardson, who had recently been hired as Mr. Barry’s deputy chief of staff, was there, too, in a room packed with constituents. At that point, the estimate for the bridge park was $30 million, funded with a mix of public and private dollars. “Folks were like, ‘Do you know what we can do with $30 million dollars in Ward 8? And you want to build a bridge?’” Ms. Richardson said. She thought: That’s not for us.

Ms. Richardson moved to Ward 8 when she was 12, leaving only to go to college and to earn a master’s degree in social work. Over her career, she has managed shelters for homeless people, run violence prevention programs and supported residents in Washington’s public housing projects. When her son was born, she moved into a duplex in Skyland, just east of Anacostia, where she still lives. A self-proclaimed eco-feminist, Ms. Richardson planted saplings in Oxon Run Park, a three-mile, 128-acre meander along a creek bed near her home. She went to endless meetings, dragging her son along. She felt called to help her community but worried about gun violence. When her son was 7, she asked him if he thought they should leave Ward 8. But he had been listening to her in all those meetings. “He’s like, Mommy, you can’t leave,” she recalled. So she stayed.

Every few years, it seemed to Ms. Richardson, somebody like Ms. Tregoning or Mr. Kratz came across the river with promises. They would solicit community feedback, publish a report and then do nothing. In that meeting about the park, all she heard was yet another promise to be broken.

“You need to know there are meetings, and then there are the meetings after the meetings.”

But Mr. Barry, who died in 2014, may have sensed an opportunity. He told Mr. Kratz and Ms. Tregoning that he would support the bridge park if the community wanted it. So Mr. Kratz headed across the river from Navy Yard into Anacostia to find out.

Over two years, while he was still working full time at the National Building Museum, Mr. Kratz met with more than 200 people in Ward 8. He met with business owners, faith leaders and elected officials. He talked to directors of local nonprofits, showed up to neighborhood meetings and presented to civic associations, always asking: Was a bridge park a good idea? “We beat him up pretty bad,” Ms. Richardson said. She had become a thorn in Mr. Kratz’s side, pressing him to answer what the bridge park would do for Ward 8. She wanted him to understand that while he may have talked to a lot of people, community members might not be fully candid with a white guy from Capitol Hill. “You need to know there are meetings, and then there are the meetings after the meetings,” she told him once.

Ms. Richardson’s attitude softened in 2012. That summer, 25 students from across the city were hired through a youth employment program to make preliminary designs for a park. Using foam board, clay and tissue paper, the students conjured a park with outdoor classrooms, shade trees, local art displays, running paths, kayak launches, and spaces for small businesses and food trucks. They presented their designs to a group of community leaders, including Ms. Richardson, who was still working for Mr. Barry. “I don’t think the children of Ward 8 have ever been invited to have that kind of competition for a real project that was actually going to come to fruition,” she said. She was proud of the students. When Mr. Kratz opened a design competition for the park, the student models were provided as inspiration.

The winning design by the architectural firms OMA and Olin and chosen by a committee of residents, features two gently sloping platforms crossing in a wide X shape, a gesture of connectivity. The student designs showed a real exuberance, “a desire to have it be a place for something to happen,” said Jason Long, the partner in charge at OMA. Similar to the students’ version, the architects’ design included an environmental education center, a community cafe, rain gardens and play spaces, a kayak launch and running paths. The goal, Mr. Long said, was to create “a destination for neighborhood life.”

The 11th Street Bridge Park, as seen in a rendering by OMA + Olin, would span the river with sloping platforms and offer play spaces, a cafe, running paths and gathering spots.

But from the beginning, this destination represented a threat to the existing neighborhood. After OMA and Olin’s winning entry was published, Mr. Long said, real estate agents started using the rendering in home listings, touting proximity to the future bridge park.

III.

By 2014, Mr. Kratz had quit his job at the museum and joined the staff of a longtime Ward 8 nonprofit called, fittingly, Building Bridges Across the River as the director of the still-inchoate 11th Street Bridge Park. Shortly after, he had lunch with Oramenta Newsome, who was at the time the executive director of Washington’s Local Initiatives Support Corporation, a federally certified financial institution that serves low-income communities. The city had added the bridge park to its budget, earmarking nearly $15 million for construction. That commitment gave the project legitimacy — “it just wasn’t me sitting in a basement somewhere coming up with this crazy idea,” Mr. Kratz said. But he still needed to raise tens of millions more from private donors to get the thing built.

Ms. Newsome had bigger ideas. She wanted a park, sure, but she also hoped to use it as a way to increase investment in Anacostia more broadly. She offered up Adam Kent, now LISC’s deputy director, to help write a so-called equitable development plan. With advice from Anacostia residents, Mr. Kent and Mr. Kratz settled on four things the bridge park needed to invest in before construction even began: affordable housing, work force development, small businesses, and arts and culture. The plan was published in late 2015, and soon after, Ms. Newsome committed LISC to investing $50 million in neighborhoods adjacent to the bridge park. It was a remarkable sum. Since 1982, when the organization was founded, LISC had spent less than $4 million in those same neighborhoods.

View over the Atlanta Beltline, an ambitious plan to create a 33-mile public access loop in the city. (Photograph by Audra Melton for The New York Times)

“When you have a shrinking city, there’s not as much to invest in,” said Ramon Jacobson, who is LISC’s current executive director. But as Washington grew, the momentum shifted. The bridge park was going to usher in enormous change for the neighborhoods east of the river, Ms. Newsome said when announcing the investment. “And the question for us was, Are we just going to shut our eyes to this or are we going to at least make a try at it?” she said at the time. Soon after, big banks and philanthropies offered support for the equitable development plan.

Without this kind of financial commitment early on, the trajectory of the bridge park could have been very different. Mr. Kratz had read a similar plan published by the much larger Atlanta BeltLine, a decades-long effort to convert an abandoned rail corridor encircling Atlanta’s downtown into a 33-mile loop of mixed-use trail. Because of its ambition, the BeltLine required a unique source of funding. City leaders decided to use something called a tax allocation district to pay for the $4.8 billion project. Land acquisition, construction and landscaping would be paid for with the increase in property tax revenue within the 6,500 acres around the planned BeltLine. It was supposed to be a virtuous circle: The BeltLine would increase property values and the resulting increase in property tax revenue would pay for the BeltLine. But this mechanism also led to gentrification, says Daniel Immergluck, a professor of urban planning at Georgia State University. Dr. Immergluck tracked home values within half-mile of the BeltLine between 2011 and 2015 and found that, even in neighborhoods where the trail hadn’t been built, those home values rose more than elsewhere in the city.

Foreseeing this, the Atlanta City Council required the BeltLine to create 5,600 units of affordable housing by 2030, when the trail was scheduled to be finished. In 2017, an investigation by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found that the BeltLine had funded only 785 affordable homes. Clyde Higgs, the BeltLine’s new CEO, blames this early sluggishness largely on the shortcomings of the tax allocation district as a primary funding mechanism. “If property values aren’t increasing and growing,” as happened during the Great Recession, “then there’s just not a whole lot of money that is going to be produced inside of the tax allocation district,” he said. There was no cash to buy land precisely when land was cheap to buy.

The BeltLine has tried to change course, with new leadership pouring more than $34 million into land acquisition and affordable housing since 2017 and, partnering with other public agencies, creating more than 1,500 units of affordable housing. Last year, the BeltLine developed a program to help homeowners stay put by paying any increase in property taxes until 2030. But the fact that the BeltLine faltered during its early years means it is now reacting to displacement, rather than preventing it. “If we just recreate segregation in a different spatial arrangement so that everything near the BeltLine is affluent and the poor folks have to move far from the BeltLine,” Dr. Immergluck said, “I’m not sure that’s an improvement over what Atlanta looked like in 1980.” The lesson of the BeltLine is simple, he said: “Acquire land as soon as you can, through any means necessary.”

The Anacostia River Festival, which is hosted by the 11th Street Bridge Park and the National Park Service, was held in April. It included a performance by the Eastern High School marching band.

IV.

I met Kymone Freeman on the patio of Busboys and Poets, a bookstore and restaurant in Anacostia, where he sat soaking up the thin November sunshine. He had been up late the night before, hosting a party to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of We Act Radio, a social justice-focused community station he founded. Even slightly hung over, Mr. Freeman radiated charisma. It seemed as if every fourth passer-by greeted him with “How you doing?” to which he replied: “Enjoying the revolution, I hope you’re doing the same!”

Mr. Kratz met Mr. Freeman at a holiday party at the Anacostia Playhouse in 2014. Mr. Freeman was working with a local public radio station to produce “Anacostia Unmapped,” a show featuring stories about the neighborhood told by longtime residents. While they were taping, Mr. Freeman’s producer gave him a copy of “Streets of Hope: The Fall and Rise of an Urban Neighborhood,” which details how residents in a Boston neighborhood formed a community land trust in the 1980s to resist gentrification. Mr. Freeman had never heard of a land trust. A form of ownership with origins in the civil rights movement, a land trust removes land on which housing is built from the profit-driven real estate market. The land itself is typically owned by a nonprofit governed by community members and developed privately, often as affordable housing. A land trust offers the radical possibility that a house or building might remain affordable in perpetuity, no matter what happens around it. Mr. Freeman was floored. He had never considered that there was something you could actually do about gentrification.

When Mr. Kratz asked Mr. Freeman what the neighborhood needed, Mr. Freeman answered: a land trust. “We have a false narrative: Gentrification is like the big giant that lives up in the hills and comes down to the city and terrorizes people,” he said. “It’s man-made. It’s not like rain and clouds. It’s not a thing of nature. It requires a different plan.”

Kymone Freeman, who founded a community radio station in Anacostia, suggested that the bridge park planners support a community land trust to create long-term affordable housing.

That different plan would eventually become the Douglass Community Land Trust. Thanks to a $3 million grant, the land trust was established as a nonprofit and bought its first property, an apartment building in Congress Heights. Today, the Douglass Community Land Trust holds 223 units in its portfolio, 69 of which are rented at affordable rates. (Mr. Freeman is on the board.) As it forms partnerships with developers across the city, it plans to add hundreds more in the coming years. Through the land trust, bridge park planners have heeded Atlanta’s lesson: Buy land as soon as possible. But time is running out. The bridge park is not the only project driving up the cost of land. As the rest of Washington becomes more expensive, white-collar workers who might never have considered Ward 8 are now willing to hop across the river. That influx has either energized investment or accelerated displacement, depending on whom you ask. New commercial and residential developments are rising in Anacostia. And, in 2020, Starbucks, that emblem of mainstream gentrification, opened its first stand-alone store east of the river.

Mayor Muriel Bowser’s administration has committed increasingly ambitious sums toward affordable housing, but it has been slow to warm to the land trust model. (Mayor Bowser’s office didn’t respond for comment.) This year, when the District of Columbia Council committed $400 million to affordable housing, it allocated just $2 million to the land trust. That doesn’t go far when the median home price in the neighborhood has surpassed $500,000.

In April 2021, Faruq Bey got a letter in the mail. The Douglass Community Land Trust was proposing to purchase his four-unit building in partnership with an affordable housing developer called Mi Casa. Mi Casa would buy and maintain the building while the land trust would own the land below it. Eventually, Mr. Bey learned, the land trust intended to help the tenants buy their building through a cooperative ownership model.

“It’s man-made. It’s not like rain and clouds. It’s not a thing of nature. It requires a different plan.”

Mr. Bey thought it sounded too good to be true. But when the land trust closed on the property in December, Mr. Bey and his three neighbors signed an agreement to pursue buying their building within 18 months. Now, Mr. Bey is working on building up his credit so he can qualify for a loan. “I thought I’d be priced out of this area,” he said. “Knowing that might not have to be the case is very reassuring.” Mr. Bey and his neighbors are talking to one another regularly now as they navigate the process of becoming homeowners. “It really made us engage with each other,” he said, adding that the land trust has given them a sense of power — a sense that they have control over their futures.

Rowing past the bridge supports on which the new park will be built.

V.

Sabrina Walls grew up in northeast Washington, D.C., near Gallaudet University, in a quiet residential neighborhood of single-family homes occupied mostly by middle-class Black families like hers. After high school, she attended a technical college and got a job at a medical supply company. At 26, she gave birth to a son, and she eventually moved to Ward 8, where rents were cheaper. Ms. Walls wanted to buy a home, to give her son the security and freedom she had enjoyed as a child, but she earned less than $40,000 a year and had racked up debt after her hours were cut. The neighborhood she grew up in had long since gentrified and rebranded as NoMa, complete with an REI store, a Trader Joe’s and a new $104 million rail station four blocks from her old house.

For decades, a local affordable housing developer called Manna had been giving workshops for low-income home buyers in Washington. In 2016, Mr. Kratz asked Manna to offer classes in Ward 8. As soon as she heard about them, Ms. Walls enrolled. One Saturday a month, for three years, she sat in class while her son played in an adjacent room. She learned about the home-buying process and eventually filed for bankruptcy to get out from under her debt. Rebuilding her credit was a long, hard process. Her financial counselor encouraged her to keep going. “He didn’t let me give up,” Ms. Walls said. “He would always try to find options anytime I felt like I wasn’t going to make it.”

Sabrina Walls, with her son, Zamir, and her boyfriend, Cedric Griffin, attended a Ward 8 homebuyers club and worked for years to rebuild her credit so she could buy a townhouse.

As she began to save money for a down payment, her counselor told her about a vacant lot where Manna planned to build 12 mixed-income townhomes with funding from LISC. The complex would be called Oramenta Gardens in honor of Ms. Newsome, who died in 2018. Ms. Walls often drove by the lot, watching as the structures took shape — foundation then frame, insulation then drywall. At some point in 2020, she decided: That’s my house. A year later, in March 2021, Ms. Walls moved in. After getting a loan from Washington’s Home Purchase Assistance Program and closing-cost support from Manna, her mortgage ended up being just under $160,000.

I visited her on a Wednesday night in November. A pot of soup simmered on the stove. The kitchen counters were covered with groceries, unopened mail, a purse and a backpack — weeknight clutter. Framed family photos hung on the walls, showing Ms. Walls and her son, now a teenager, when their faces were softer and rounder. As we chatted at a bar table in the kitchen, Ms. Walls’s boyfriend, Cedric Griffin, sat on a couch, typing on a laptop. Mr. Griffin, who grew up around the corner, said there was already “plenty of gentrification going on” in the neighborhood — with or without the bridge park. “I want to see some improvements in the community,” he said. “Not to the degree that it just runs everybody who’s already here out, but I do want to see it be better for everyone. I want those who are coming in to feel like it’s a comfortable place for them to be. I want those who are already there to feel like I don’t have to be uncomfortable in the place that I’ve grown up in.”

This is the razor’s edge of gentrification, and capitalism does not tread it well. “The free market is going to do what the free market’s going to do,” said Mary Bogle, a researcher at the Urban Institute in Washington who studies poverty and economic development. “And that means that the rents are going to go up the more attractive a neighborhood is made.”

Ms. Bogle has spent five years studying the impact of the bridge park’s equitable development plan. The results are impressive, she said. To date, $85 million has been invested in Ward 8. LISC has invested $72 million, financing the creation of nearly 835 affordable rentals and 59 homes for sale, and supported the development of 1.7 million square feet of office and community space. Through partners, the bridge park has explained tenants’ rights to thousands of renters. It got funding for a construction work training program, which more than 270 people have completed; they will be first in line for jobs when it comes time to actually build the park.

With nearly $300,000 from the bridge park, Manna’s Ward 8 home buyers club has graduated more than 800 families, and 104 of them, including Ms. Walls’s, have gone on to purchase homes. Almost 700 small businesses have received loans or technical assistance totaling nearly $888,000. Four hundred families receive a weekly box of produce grown at an urban farm. In early 2020, as the coronavirus spread, the bridge park helped start an unconditional cash transfer program, ultimately distributing more than $3.2 million to 600 families in Ward 8.

There are other less tangible benefits, too. Shortly after Vaughn Perry, a longtime Ward 8 resident, began working for the bridge park as its equitable development manager, he started workshops to teach residents about community organizing and the city planning process. More than 70 residents from Ward 8 have taken the workshop; two have gone on to run for public office. “People understanding that they have power to invoke change in their own community is the thing that resonates the most to me,” Mr. Perry said.

“People understanding that they have power to invoke change in their own community is the thing that resonates the most to me.”

Being part of the Douglass Community Land Trust stirred something in Mr. Bey. He loved the fact that if he ever moved, his unit would remain affordable to the next person. So he decided to enact that pay-it-forward ethos and started volunteering with a local group to organize tenants fighting for better living conditions at a nearby apartment complex. “We’re trying to show people that a lot of things are in their own hands,” he said.

Oxon Run Park is Brenda Richardson’s favorite place in her neighborhood, but, after initial skepticism, she’s come to embrace the plan for the 11th Street Bridge Park, too. “The community said this is what they want.”

Most of the physical infrastructure in the United States was not built with meaningful input from the communities it affected. After the Federal-Aid Highway Act passed in 1956, Black and Hispanic homeowners sometimes found out that they were losing their land only when highway department appraisers showed up on their front lawns. Until 1970, most public agencies didn’t even have to ask for public feedback before beginning a major project. Even today, public input is often a box-checking exercise, something to be rushed through on the way to the actual planning done by engineers and other experts who shape our cities. The bridge park shows that something else is possible: People in a community can be engaged and build a vision based on what they want and need and, in doing so, grapple with some of society’s most basic problems — how to provide affordable housing, good jobs and a sense of connection to the place where you live.

Mr. Kratz and others are making progress in Anacostia, Ms. Bogle said. But even there, they can only do so much. “Are they even making a dent in building equity overall in the surrounding neighborhoods? Likely not,” Ms. Bogle said. “Capitalism can’t help but pick winners and losers. And these projects are doing a valiant effort to try to stem that tide, but it’s a huge tide.” A 2021 report noted that the number of home buyers club graduates with the ability to buy homes had fallen, in part because it was harder to find affordable properties. And increasingly expensive housing west of the river puts more pressure on Wards 7 and 8. In 2019, Mayor Bowser set a goal to build 12,000 units of affordable housing throughout Washington. Three years later, only the neighborhoods east of the river have met production targets, leaving the white, gentrified neighborhoods in northwest Washington largely untouched.

Ms. Tregoning, the city’s former planning director, imagines that the bridge park could at least be a model for other communities. The park’s budget is roughly $177 million, with $45 million from the city. By the time it breaks ground in 2023, some $85 million of that will have already been spent on affordable housing, job training and community empowerment. Consider the $550 billion in new federal spending on infrastructure that Congress passed in November, she said, and imagine projects all around the country conceived not simply as physical assets, but as community and social ones, too.

But now, Mr. Kratz needs to build the park. If he doesn’t, the project will become yet another broken promise for Ward 8 residents — and a cautionary tale for those outside of Washington. Infrastructure reuse projects are hard enough. There are so many bureaucratic hoops to jump through, engineering problems to solve, funders to please. “You’re doing this impossible thing,” he said, “and now you also have to stop gentrification.” Mr. Kratz feels the pressure. “If we build the park, this can be the model,” he said. “If we don’t build the park, you can hear the narrative already: ‘Well they got busy with the community land trust, doing home buying, they took their eye off the prize.’”

Brenda Richardson wants to see the park built, too. We met on a glorious fall day in Oxon Run Park, her favorite place in her neighborhood, where she goes to recharge and reflect. I asked her the question she asked a decade ago — what could Ward 8 do with the millions committed to construction? Did it really need a bridge park? She paused. Two men with leaf blowers corralled the ochre and crimson leaves from towering maples into tidy piles. “The reason I’m not able to pooh-pooh the 11th Street bridge is that the community said this is what they want,” she said finally. “What I would really like to see is that we get to enjoy it. We get to stay here and we get to live here and enjoy it.”

Read More at NY Times HERE